By Bill Templeton/Music Maker Magazine, April 1983.

By Bill Templeton/Music

Maker Magazine, April 1983.

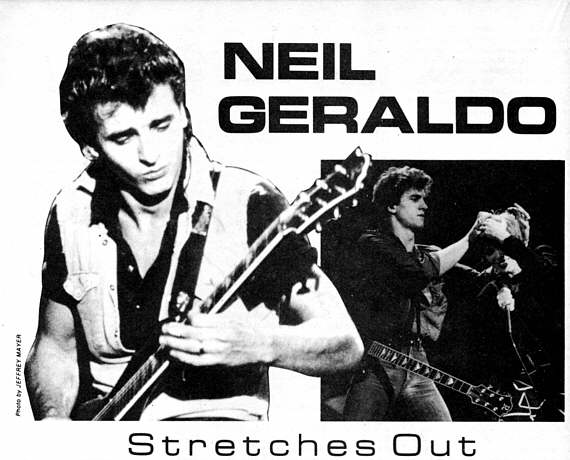

In 1978, Neil Geraldo was just

beginning to gain a little bit of personal recognition for his talents. He’d been playing the guitar since he was

seven years old... professionally since he was fourteen, and for the last ten years Neil

had been playing in high school groups, local club combos and soul bands. Through

perseverance and determination, he and his various musical configurations had managed to

release regional 45’s in Cincinnati, Cleveland and assorted locales throughout the

East and Southeast. In 1978, on the strength of two years’ of performing in his first

“big time” tour with part time rock legend Rick Derringer, Neil Geraldo was

finally becoming noticed.

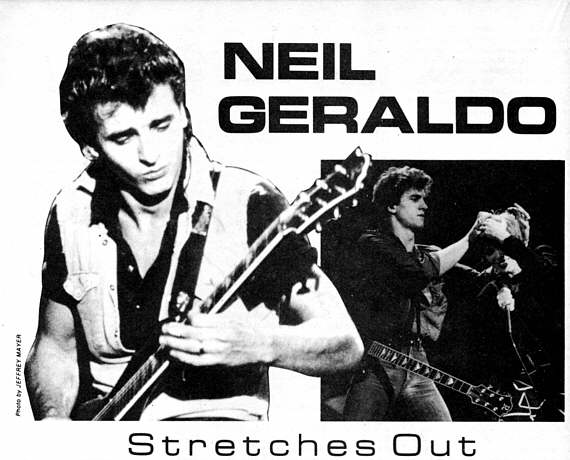

On stage, in those days, Geraldo was like a lot of other young

guitarists trying to make the grade - he was hungry. He played with a fiery passion fueled

by the will to succeed, or more importantly, to just be given a chance to strut his stuff;

a chance to show what he’d learned during his impressionable decade on the road; a

chance to demonstrate to anyone who might be interested that he had what it took to make a

career out of what most people had a hard time sustaining as a hobby... music.

Geraldo’s ascension was pretty much by the book. Play and

learn... continually, until someone noticed and you could move up another rung. That

someone, in this case, was Rick Derringer, but Geraldo committed one fatal mistake during

his apprenticeship with Derringer. Something he hadn’t fully counted on. The kind of

judgement error that anxious up- and-corners usually and conveniently forget about...

Geraldo showed up the boss! (Number two in the “Don’t” list, right behind

messing with the boss’s wife). So, as a result of Nell’s inspired and

unintentional determination, he was demoted to piano player on the one LP he recorded with

Derringer, Guitars and Women, and later given his walking papers.

This would probably be the end of a sad story in most circles,

but it was to later turn Into the proverbial silver lined cloud for Geraldo. Because while

Neil was packing his bags, Rick Newman, famed proprietor of New York’s ‘Catch A

Rising Star’, was on the other side of the continent closing a deal between Chrysalis

Records and his new-found star, Pat Benatar. In order to facilitate the recording of

Benatar’s first album, a full-time band was needed, and this is where Neil

Geraldo’s name resurfaced, this time from the lips of ace producer Mike Chapman. It

was Chapman (well known at that time for his production work with Blondie, among others)

who suggested Neil, not only as a lead guitarist, but as a complete musical director, as

well.

It was a match made in heaven. Literally! As it turned out, Neil would eventually marry

Pat, binding their relationship on both a personal and professional level. The lyrics to

the band’s third LP Precious Time are ripe with references to the duo’s intimate

ups and downs, as it was recorded at the crossroads of the group’s career. Having

solidified their commercial position in the marketplace with In The Heat Of The Night and,

especially the platinum plus follow-up, Crimes of Passion, both Benatar and Geraldo —

who were new to, the rigors of rapid success — found themselves at their wit’s

end. They had just finished a grueling tour that, at one point, found Geraldo playing his

guitar with a broken wrist, casted to the elbow of his picking hand, and at another point

found Benatar flat out cold on a Lakeland, Florida, stage (due primarily to exhaustion).

Their newfound relationship was on the skids, with both parties living in separate

houses, and the only thing to look forward to was another hit LP and another long,

seemingly insurmountable tour.

That they kept their collective heads and held the band together at all is a testament to

Neil’s and Pat’s desire to survive within an industry that is notorious for

burning out the creative resources of its young early. A long-awaited break was the most

helpful factor in allowing the Benatar Band time to regroup and allot themselves some

necessary breathing space. It was during this period that Neil and Pat realized that their

relationship was indeed the most important thing they had going, so they consummated

their bond In manage. Probably figuring that with the Crimes of Passion and Precious Time

tours they had already braved the worst — the rest was Easy Street.

During this rest period, however, Geraldo was still hard at work on outside projects.

Following the Precious Time tour, Neil worked a rare (for him, anyway) session/gig with

Kenny Log-gins (on High Adventure) and handled the first in a series of production chores

on the successful John Waite (ex-Baby) solo LP. Neil directed and produced the Benatar

Band’s most recent release, Get Nervous, and has recently assisted in producing an

HBO special which will feature the band live in concert. The band’s 1983 tour is now

underway, and, on top of all this, Neil has just designed a guitar that should be on the

marketplace by the year’s end.

The

following interview was conducted during a break in the filming of the HBO special slated

to air some time this summer.

MusicMaker: Although you’re involved in everything from

production to composing, you’re primarily known as a guitar player. How did you first

pick one up?

Geraldo: It was mostly my father. Being first generation

Siciliano, my father always loved the guitar and singing. He would say, “Why

don’t you play guitar?”, and I’d say, “Aw, I don’t want to play

guitar, I want to play baseball or football.” But I finally got around to it when I

was about seven years old.

MM: How about

your first pro gig?

NG: I remember

the first gig I played was in a bar in Cleveland. I was pretty young, 15, I think. My

Uncle Tim was in a band and he’d always sneak me in the bar early to help move

equipment. The club owners always thought I was there to move amps around, and then

they’d find out I was In the band. That started it all.

MM: What kinds of

music were you playing then?

NG: Yardbirds. I

remember we had to play “Nazz Are Blue” about 9,000 times. But we’d play

the Yardbirds, Sam Cooke, James Gang, some weird stuff, actually. We had a good time. It

was really wild.

MM: How did your

parents feel about your being 15 and playing in the bars?

NG: Absolutely

hated it! They didn’t think I’d love the guitar as much as I did, I guess. I

didn’t think so, either. But everyone goes through that time period with they think

they know everything. It’s tough for all adolescents, and I was no different. I gave

my parents a mess of shit and a hard time, besides doing something as wild as playing in

bars. I mean, I’d be gettin’ In trouble all the time, comin’ in late,

stayin’ up all night, then skipping school to jam all day. I played in a lot of bands. I went and lived in

Florida for six months and played in a lot of bands down there. In Cleveland we used to

release 45’s and singles, y’know, just regional things, and take them around to

the record stores and stuff like that.

MM: How did you

get hooked up with Rick Derringer?

NG: Well, I was

playing bass In a bar and somebody told me that Edgar Winter needed a bass player, so I

said, “Yeah, sure give him a call, It might be fun for a while.” So the guy

comes back and says that Winter doesn’t need a bass player but Rick Derringer needs a

guitar player, and I go, “What, are you nuts? I’m a guitar player!” The guy

says, “Well, I never heard ya,” and I said, “I know you never heard me, who

cares? Can you call him back and see if you can set something up?” So he says, sure,

and I went up there and I didn’t come back.

MM: What

convinced Rick you were the man for the job?

NG:

He was auditioning a lot of guitar players, but I think the thing that made Rick want me

was my attitude. I was a little different from everyone else that was there. Besides, I

could play the bass and piano, and I could sing a little bit, so I was like a utility man,

and I think he liked that idea.

MM: The first

time we spoke you told me that Rick wasn’t too comfortable with your stage presence,

your gyrating and scene-stealing and all.

NG: Yeah, to a

point that was true. It wasn’t so much my guitar playing and stuff, because I think

Rick always knew that eventually I would be becoming stronger as a guitar player and

I’d. have to go out on my own. But he taught me some very valuable things. And what

happened was, when I started coming through like that, as far as my own individuality, it

became very difficult to get myself represented on the album with Rick. Because he’s

the main player, you back him up, and that’s what I was to him... a utility man.

MM: How long were

you with him?

NG: Two years.

And almost all of that was on the road.

MM: Did you find

yourself getting more aggressive on stage with Derringer?

NG:

Not really. I

was basically the same. Rick always liked what I did then. He liked it ‘cause I was

wild, I was dancin’, doin’ whatever I wanted to do. He liked that to a certain

extent. Because It pumped him up. He was, maybe, feelin’ he was getting older and he

had this young blood pumpin’ him up. Which is a very smart thing to do. And I could

see his point for that. But I really haven’t changed much from the clubs I was

playing at In Cleveland, wild like a maniac. And when I joined Rick’s band..,

actually there’s no difference.

MM: You must have

found it frustrating to tone things down for the benefit of Pat’s band.

NG: It was

frustrating to do that. But I believe it was the right thing to do. There was a lot of

heat goin’ around about trying to take away from Patty’s performance, which was

never in anyone’s mind. All we tried to do was come out like we really are and not be

insincere or fake or try to fool people, like we’re not having a good time.

MM:

I’m glad to hear you’re going back

to the uninhibited performances.

NG:

We went back and I wouldn’t have done it

any other way. I felt kind of bad, like we slighted the audience in a way, by not giving

it all on the last tour — the last two tours. The kind of energy we had for the

first. I really was goin’ through a complex thing in my mind. I just basically put my

head down and nose-dived and said, “O.K., I’ll just ground it out this way,

it’s O.K.” Until I just got so frustrated and so mad that Patty and I were

saying “Goddammit, we’re being stupid. We’re being like an aged band that

just doesn’t know what to do with themselves.”

MM: It was very hard for

you at the time?

NG: It

was very, very tough. I didn’t even really want to do the (Precious Time) record at

that point — I was very mad. I was walking out every five minutes. I was very

disappointed. I like the way it came out, though. Some things really show what that record

is about. Like “Promises in the Dark”, “Precious Time” and even

“Fire and ice.” It was just very tough for everybody, though.

MM: That

got smoothed out by the next album?

NG: It

got smoothed out after the tour. That’s when I went and produced the John Waite

record in New York. When I came back with John, who I learned a lot about and who was

really wonderful — when I came back from New York to California to get ready to do

the record, I said, “Listen, this is the way we’re gonna do it this time.

Let’s go.” Then it was back to the way it was in the beginning, which made it

feel great. And it sparked much better now than it has for the last couple of years.

MM: How

does your record company and management view you doing something different?

NG: They like the idea,

obviously. If it works for them, they’ll love the idea. Obviously I’m gonna try

to achieve success of a large level. But I don’t really absolutely need it and the

management or record company would be happy as long as I keep the Benatar band moving and

keep this up to standards that we’ve always tried to achieve. I think I’ll be

able to do anything.

MM:

Looking back on the LP’s, how do you feel

about them in retrospect?

NG: With the

first record, I don’t think we were even a band at that point. We had the different

drummer. The drummer that played on the record played great on the record, but as soon as we started rehearsing it

wasn’t cutting it. We thought we had to have something stronger. But for that record

it was really great.

MM:

Because of the strong influx of female artists

at the time, were you surprised by Pat’s success?

NG:

I didn’t know what was gonna happen and

then when it started going completely wild — it was a shocker. You don’t have

any idea at that point, but you never think about a huge success, which did happen. But on

that first album, the band wasn’t really together. It was a band but it wasn’t

really a group until it started touring. As soon as that tour was done, it came time for

Crimes of Passion, which was the time for me to get it really going. The pressure started

being applied In that respect. I was wild, I was stayin’ up so late. The first record

had a lot of tunes already picked. Patty’d already chosen, Chapman already chose some

songs, so for Crimes of Passion we wrote more songs. Why should we do other people’s

songs when we can represent our own, and translate them our own way? So we started writing

them, but I think I would do something different on that second record If I had another

chance.

MM:

Pat had implied that she wasn’t all that

happy with it, either.

NG:

I think the selection of the songs on the

record were the best they could possibly be at that time. I just feel a little

disappointed with “Hell Is For Children”. I wish I could have gotten an even

stronger performance with that. I think the performance of that is great; it’s

tremendous. But I always believed that we could have even done it a lot better.

MM:

But overall?

NG:

I think It did satisfy the band. There was an

extreme amount of pressure at that point. It was the second album and the record company

is saying, “This is the most special album.” And then the third one is

“really important”. Then, “Hey, the fourth one!” Little ways to make

you nervous. But that (Crimes of Passion) was the

MM:

The old sophomore jinx?

NG:

Yeah, that was tough. That was a really tough

place to be. We tried our best and we were lucky to be commercially successful.

MM: The third LP, Precious Time was even

tougher, wasn’t it?

NG: I think that

was a point of confusion In everybody’s life and in everyone’s thinking. I mean,

I was confused, Patty was confused, we didn’t know what the hell we were gonna do,

relationshipwise. We didn’t have time to sit back and think — we were on the

road constantly, 24 hours a day. And we knew that when we did this record we’d have

to go out and tour and I wasn’t becoming a big fan of touring in that situation. It

was getting weird for me. It was getting weird for Patty and everyone else in the band,

and everyone gets affected when myself and Patty are having a tough time. You know, if

I’m having a tough time, the band will show it.

MM:

How did you feel about the third album?

NG:

I thought it was good at the end when we got

done with it. I said, “Yeah, this is good.” I singled out special songs that

were very important, and the rest were, I considered, some of the weakest material I ever

wrote. I was just in total confusion. I couldn’t get it straight in my mind

what the hell I should be writing, what I should be doing. If I write a lyric that in some

way is gonna make Patty feel uncomfortable about singing, it’s gonna make me stop and

not do it.

MM:

Are you primarily responsible for the majority

of the lyrics?

NG:

I’d say, maybe 75%. Sure, I do quite a

bit of the lyric writing. We write together, Patty and I.

MM:

How do you write, keeping your

responsibilities in mind — yet liking different kinds of music at the same time?

NG: That’s

where Patty is the equalizer. She likes pop songs. She likes commercial songs, she also

likes the weird stuff, but she really loves the pop things and the hard rock side, too.

When I come in and I say, “Hey, I like this, let’s play it backwards or

something,” she’ll go, “No, forget it, get a drink or something.” So

we’ll equalize it out. We’ll maybe use a little of it and then we’ll throw

a little away. We’ll just use half of it. But

the band will be branching out and opening up some in the future. If I don’t decide

to do it myself. It would just be tremendously too weird and the record company would chop

my legs off or something — I think we will eventually approach that, though. That may

be becoming a bigger part of the music because I’m really worried about being

stagnant. I love change — I’d like to change with every record.

MM: Do you think

you might have to do something on your own, like a solo LP, to get that kind of

satisfaction?

NG: I think so.

I’m absolutely certain I will, I mean it. I don’t know when

MM: The fourth

album, Get Nervous, how did you prepare for it?

NG: I think

it’s the best record we’ve done. I really feel strong about this one. I like the

addition of the keyboards — I thought they helped out a great deal. We’ve always

had them, I play keyboards, but I don’t play any, good I just screw around on the

damn things. So we got like a real guy to come in and play keyboards. I can take the

weight off myself — be more of a producer — get more performance from everyone

else and not have to worry about myself playing the other guitar, the keyboards and all

that. I don’t want to do that anymore.

MM: What about

the future? Any more production jobs lined up?

NG: Yeah, some

things now but I have to go through so many tapes to really sit down and see. I like the

idea of new artists.

MM: How did the

John Waite LP come about?

NG: That was

Chrysalis’ idea. Along with John.

MM: Was that to

keep you happy, as a growing artist?

NG: No, not

really. The record company always felt the Babys were a great band but they needed more

zip, more punch. They needed somebody to be around to help with the songs, to arrange, to

do that end of it. So what happened was Jeff Aldridge thought it would be a good idea for

me to do the job. I was young, the same age as Waite. I was hungry...

MM: You went for a much fuller sound on that LP?

NG: Absolutely. I

tried like hell every moment to open it up as wide as it could be.

MM: Why are you

so interested in producing?

NG: I think

that’s an obsession with me not being able to sing as well as I would like to. Since

I can’t sing, I really admire singers more than any

MM: Can you see

yourself becoming strictly a producer in the future?

NG: I don’t

see myself not playing. I don’t think that will happen. The facility for which I will

incorporate that is kind of hard to think about.

NG: Kind of. In a

way that’s true. Yes.

MM: So you may

even move on to other things besides production?

NG: You’re right. I

mean, I will do my little fun stuff in my spare time. Like I told Pat, when she asked me

what I wanted for Christmas, that a video camera would be great. But I’m gonna take

pictures of my dog. I’m gonna get it to growl and show his teeth and look real

serious and stuff, and then I’m gonna go in my little room and put music to it. I

don’t know what’ I’m gonna do with it. I’ll do my own little Fellini movie.